You never forget the first time something made of metal looks back at you.

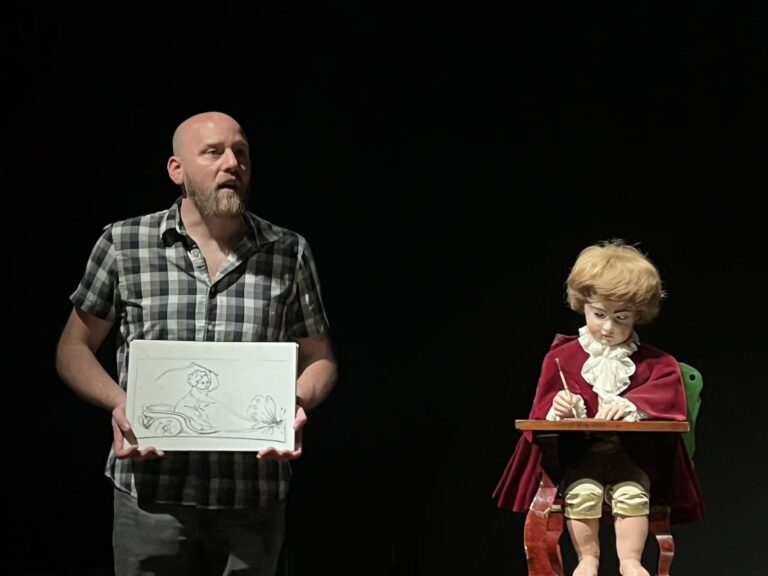

In a quiet, private gallery tucked into a concert hall in the heart of Shanghai’s new district, he sat perfectly upright at his writing desk, silver wig curled over plump cheeks, a ruffled collar blooming from a burgundy jacket tailored in the European style. His hand traced confident contours, sketching a small dog and the line Mon Toutou—“my doggy.” Then, suddenly, he blinked and nodded. I remember the crowd gasping. I was fourteen, standing in awe as this “boy,” not-quite-human and not-quite-toy, came to life before me. The guide told me he was an automaton—a “self-moving” mechanical device designed to mimic human or animal actions—and that he was built by a contemporary Swiss master named François Junod, based on an exceptional design from the eighteenth century.

This machine was invented by the Jaquet-Droz,” the guide said, “or Ya Ke De Luo, as their greatest admirer, the Chinese Emperor Qianlong (reigned from 1735 to 1796), used to call them. The Swiss family invented the sliding piston whistle to make mechanical birds sing and designed automata that could write, draw, and play music.”