A new study from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has shown that specific bacteria living in the upper small intestines of malnourished children play a causal role in stunted growth and other damaging side effects of malnutrition. The knowledge could lead to better therapies for such children.

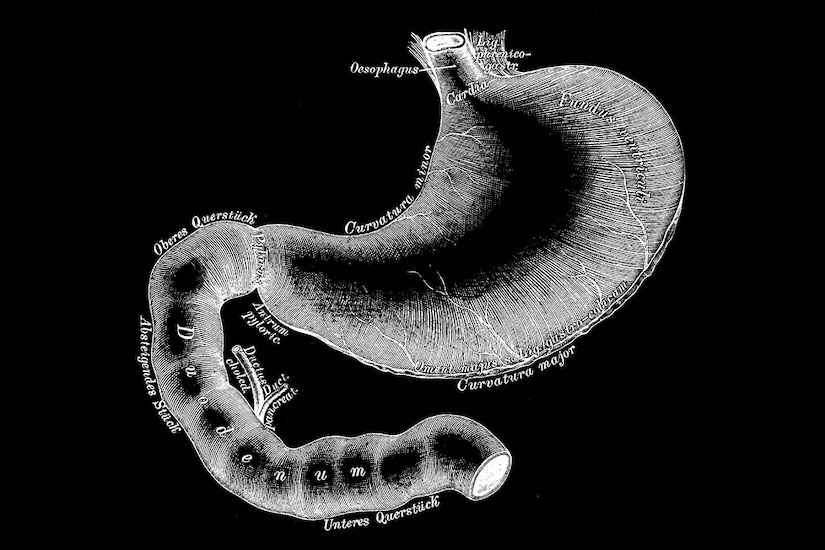

The gut microbiome has a symbiotic relationship with its human host. Evidence is emerging about its critical contributions during the early years of life to healthy growth and development. Much research involving the gut microbiome has focused on bacteria measured in fecal samples, which are not necessarily representative of the microbial communities living in different regions along the length of the gastrointestinal tract. The researchers were interested in the upper small intestine — the region of the gut immediately following the stomach — because it is largely unstudied and because there were hints that it could play an important role in malnutrition.

“Our study provides strong evidence that there is more to stunting than the conventional culprits that we traditionally blame for the problem — food scarcity, poor sanitation or a contaminated water supply, for example,” said co-author Michael J. Barratt, executive director of Washington University’s Center for Gut Microbiome and Nutrition Research.